I have been out of the social media limelight for the past 6 months. In the face of the incessant and at times overwhelming discourse around GenAI I reacted – like I suspect many colleagues – in a slightly antagonistic fashion. I felt a compulsion to slip unseen in my empirical work and educational program development, taking time to build a conceptual and practical understanding of the current moment.

It must be said that the explosion of advice around GenAI in education over the past two years – from scales to lanes and a multitude of related frameworks – answered a clear mass demand made urgent by the perceived threat to the integrity of the assessment process. Many excellent colleagues and consultants are meeting this demand earnestly, trying to shift the debate’s emphasis from damage control to cautious optimism, framing the current moment as a window of opportunity for a more ambitious reform of assessment as a “programmatic” endeavour that creates comprehensive and multi-dimensional profiles of student progress, rather than snapshots of achievement under artificially secure conditions, which AI has made very difficult to uphold.

For what it’s worth, I also took part in several discussions on GenAI and assessment which on one occasion produced – I would argue – valuable advice for universities.

However, my interest as a researcher of educational technology lies elsewhere. The most pressing question for me is a mundane and sociological one: how is generative AI finding its way into education systems, off the back of pre-existing economic and institutional arrangements?

I find this question important because nothing happens in a vacuum, and it would be unwise to approach the challenge at hand oblivious to the dominant digital economy paradigm in which GenAI has emerged, with its attendant cloud monopolies and its platformed ecosystems of captive developers and locked-in users.

My modest attempt to develop an answer has materialised in the form of two research projects. The first is 3-year Discovery Project (DP) funded by the Australian Research Council (ARC) involving three schools in Victoria, led by Prof Neil Selwyn at Monash University, while the second is a smaller one-year study on how GenAI is changing learning and teaching for the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) examination.

It is too early to share official findings from both. What follows is therefore a general reflection on the current state of GenAI in education, informed by preliminary and scattered “moments” of discussion, reading and empirical engagement. In particular, I wish to share some thoughts on the “innovation model” of OpenAI’s custom GPTs and AI assistants in education.

OpenAI as platform ecosystem

ChatGPT remains, as I write this, the most popular generative Chatbot by user numbers and daily visits. What is equally well documented is that OpenAI has all but abandoned its original mission vaguely aimed at the development of an Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) for the “greater good” and is now aggressively committed to the commercial exploitation of its proprietary models. A turning point in this transition was indeed the launch of the OpenAI custom GPT platform which enables developers with paid-for access to the OpenAI API to create, without any substantial programming skills, a conversational Chatbot by fine-tuning an existing model and training it on a custom dataset.

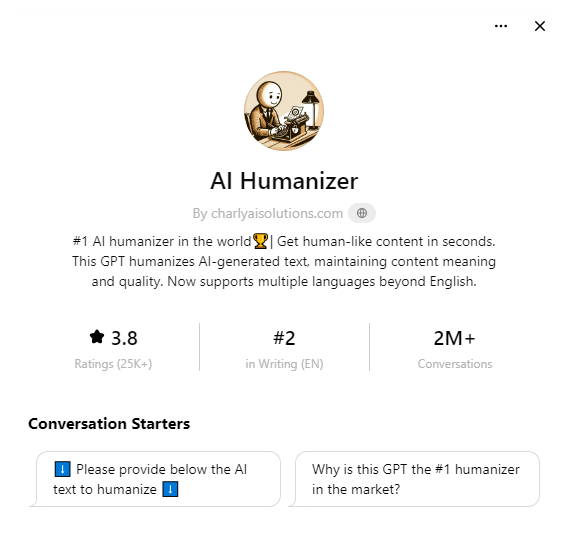

Custom GPTs are (potentially) significant from a business perspective because they are meant to operate as apps which can be developed by plugging directly into the OpenAI ecosystem. An initial search on Explore GPTs (chatgpt.com) revealed hundreds of custom GPTs with the word “Education” in the description. These range from multiple choice question generators to “Christianity” bots. However, these explicitly educational bots do not seem to attract many users. The most popular one – a bot that promises assistance “on everything education” – sports a meagre 1K+ conversations. Interestingly, educational bots pale in comparison to “humaniser bots” that promise to make AI-generated text more difficult to identify.

Alongside custom GPTs, which can be created by virtually anyone with a premium subscription, OpenAI also allows better-resourced customers to develop their own discrete “AI Assistants”. Compared to a custom GPT, an AI assistant requires more advanced development skills but promises in return more freedom. An AI Assistant, for example, can be embedded in other applications and websites.

Both options – custom GPTs and assistants – are available to users with a paid plan, such as ChatGPT plus or the API pay-as-you-go model. However, the most robust privacy safeguards and scalable features are only offered to Enterprise customers. Since January 2024, several universities have purchased an Open AI’s Enterprise license including the University of Oxford, the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, the University of University of Texas at Austin, Arizona State University, and Columbia University in New York.

In all scenarios, from the lowest API access tier to the highest enterprise one, proprietary assets and infrastructure must be hired from OpenAI’s closed development environment according to a Software as a Service (SaaS) model. Consistent with this model, monetisation may occur in two ways: on a revenue share basis and/or through the payment of licensing fees. In the case of custom GPTs, OpenAI operates as a traditional intermediary platform retaining total control over a single point of access: a paywall. Users pay directly OpenAI to use a Custom GPT and a portion of that revenue goes to the developer. In the case of fully custom AI assistants developed through an enterprise license, organisations pay OpenAI for API access and data control but are then free to either charge directly their customers for usage, or in the case of the universities mentioned previously, to offer custom affordances for administrative staff, research and teaching staff, and students.

Anyone familiar with the trappings of platform monopolism will recognise the pattern. In all possible licensing and revenue-sharing scenarios OpenAI’s maintains unrestricted control over model training and the development of API frameworks, which translates in immense competitive advantage. If a custom GPT or AI assistant is viewed as a promising business venture, nothing can stop Open AI from developing its own version which can be monetised more effectively as a fully proprietary offer. The recent launch of ChatGPT Edu – aimed at educational institutions “that want to deploy AI more broadly to students and their campus communities” – is a case in point. This is certainly a compelling proposition for administrators eager to adopt the technology but reluctant to deploy the internal resources for a custom enterprise solution. The convenience comes of course at a price, which is the familiar Faustian pact of platformisation: infrastructural dependencies and the imposition of a rentiership relation that percolates from strategic decision-making all the way down to the level of pedagogical and assessment relations involving staff and students.

Education is building a moat for OpenAI

A year ago, in May 2023, which in the compressed timeline we are in seems to amount to 5 years of “regular” time, a leaked Google memo claiming “We Have No Moat, and Neither Does OpenAI” made the headlines. The memo revealed a creeping concern within the ranks of many technology companies investing heavily in AI: the pace of innovation of large language models is so fast and granular that it will be impossible for companies to maintain a competitive advantage, i.e. “moats” that can keep at bay smaller start-ups churning out open-source models which are “faster, more customizable, more private, and pound-for-pound more capable.”

A year has passed, and the “no moat” argument is worth revisiting against the background of the monetisation and licensing efforts I summarised in this post.

Despite being the place where the memo originated, Google is arguably a case apart because its interest in AI, while enormous, is somewhat ancillary to its core businesses: search and cloud infrastructure. However, as far as Open AI is concerned, a moat is definitely being built following a textbook implementation of platformed and infrastructural monopolism: the tiered licensing structures, the timid attempts to launch an “app store” of custom GPTs based on revenue sharing, and the creation of an enterprise-level ecosystem where large and medium-sized organisations become invested in – and dependent on – a proprietary environment.

Open AI’s retrenchment into the comfort of familiar platform economics can therefore be read as a defensive and conservative move that hides a growing anxiety about the real-world viability of generative AI, with companies and users beginning to realise the limitations of a technology that promised to deliver “magic” through universal applicability and knowledge but is proving tricky and laborious to tame. As this recent Bloomberg article puts it:

When sweeping, idealistic dreams trickle down into sales and marketing channels, AI’s potential uses become unclear. Framing AI as a general-purpose Swiss Army knife for productivity inevitably leads to paralysis for its end users: Where do you even start with a technology that can do everything?

Reacting to these early signs of disappointment, and lacking other revenue streams like Google, OpenAI is therefore frantically capitalising on the residual yet still-going-strong hype by building a platformed moat that has a clear goal: to trace a path towards “hypothetical” long-term monetisation by locking in developers and corporate license holders, who will hopefully test the commercial viability of genAI through granular innovation as long as that innovation takes place within a closed development environment. Education is proving to be a prime site for this exploitative dynamic, offering opportunities for model customisation and experimentation that target two of the most enthusiastic populations of early adopters: students under the economic and social pressure to “achieve” and overworked educators desperately seeking efficiencies.

In conclusion (a temporary one – I hope to share more in the coming months), the education sector and the associated ed-tech industry are helping build a moat for OpenAI. The universities inviting research and teaching staff to identify and test application scenarios for generative AI; the scores of custom GPTs dedicated to various aspects of education, from language learning to research literature summarisation and essay writing; the tech-savvy educators and consultants developing curricula and models of professional practice. All of it represents “epistemological” free labor that creates the much-needed network effects underpinning crowdsourced value creation – value which will be captured and monetised when the time is right.

The rise of a platform economy of gen AI in education raises well-trodden questions about monopolism, exploitation, extraction and democratic governance which I and many others have explored at length – in education and more broadly. The identification of appropriate responsibilities and safeguards is a complex and fraught debate that is too easily dismissed as backwards and anti-innovation. I personally feel that over the past two years these questions have been drowned out by the noise, with many critically minded researchers struggling with wave after wave of hype and, in many cases, experiencing a genuine fascination for the augmentative opportunities offered by this new technology. As the hype begins to partly dissipate, it is time to resume where we left off. There is so much work to do!

Leave a comment